Principle 01

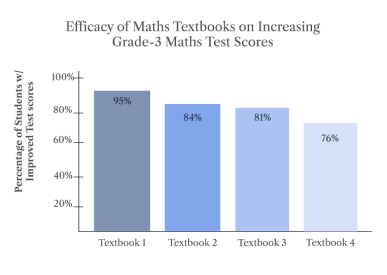

The type of findings that evidence users find useful may differ, ranging from student outcomes to teacher engagement. Evidence creators should aim to gain a full understanding of what indicators are relevant from an efficacy perspective.

User research can help you understand the preferences of different audiences for the types of findings that are relevant to them. Evidence creators have access to a toolkit of research methods to discover the behaviors, motivations, and needs of different user groups.

Principle 02

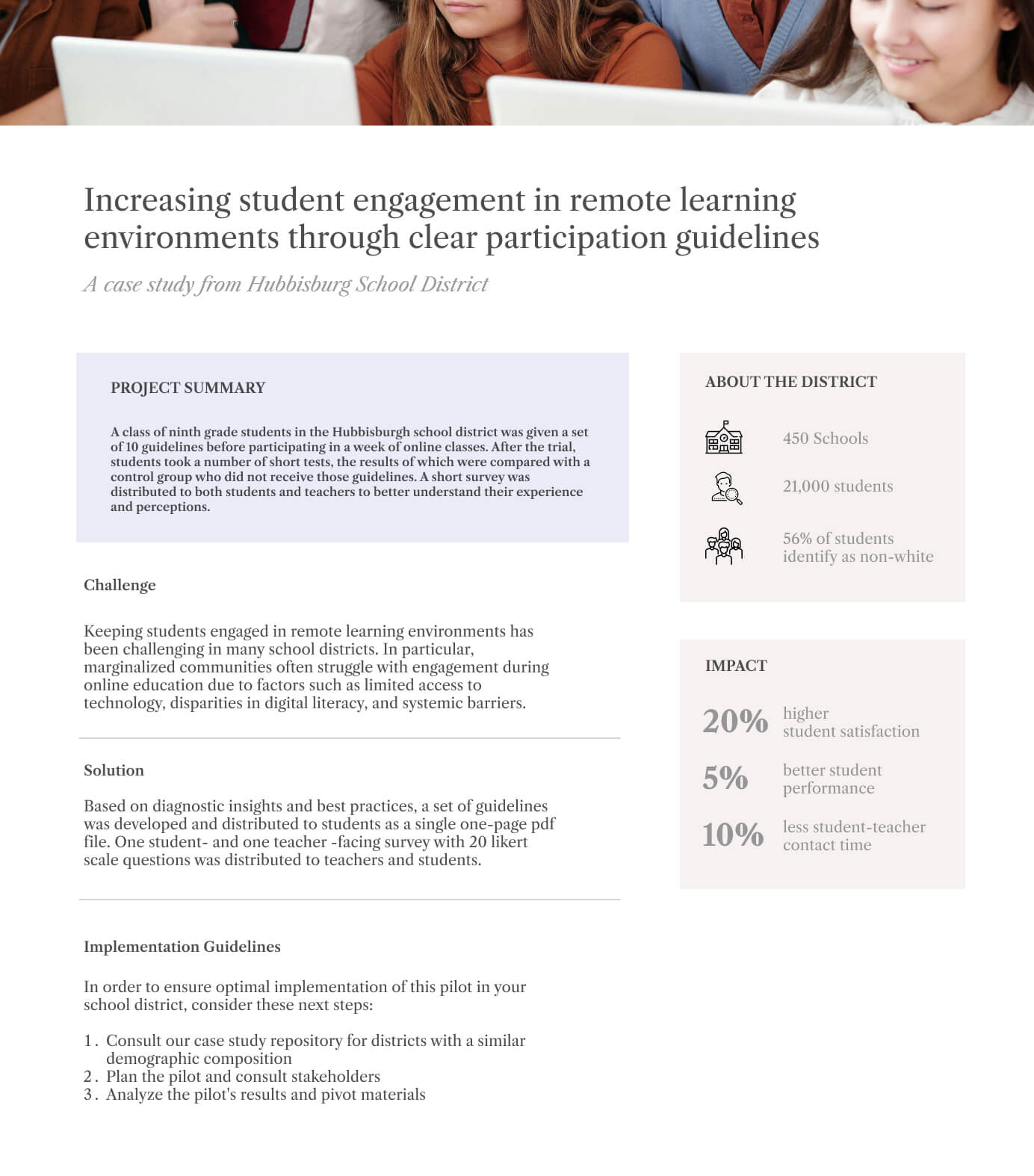

As an evidence creator, reporting findings accurately is essential to reduce the likelihood of readers misinterpreting results.

One common misconception is presuming causality where only correlational evidence exists, for example, in longitudinal or natural group studies (a longitudinal or natural group study involves observing and analyzing a group of participants over an extended period to assess changes, patterns, or developments within the group dynamics or behaviors). Experiments are the only research design that can demonstrate causality, where you manipulate independent variables and observe the corresponding changes in dependent variables, allowing you to establish a causal relationship between the two.

To avoid misrepresenting results, evidence creators should adjust their language to describe causal relationships and correlations respectively.

Principle 03

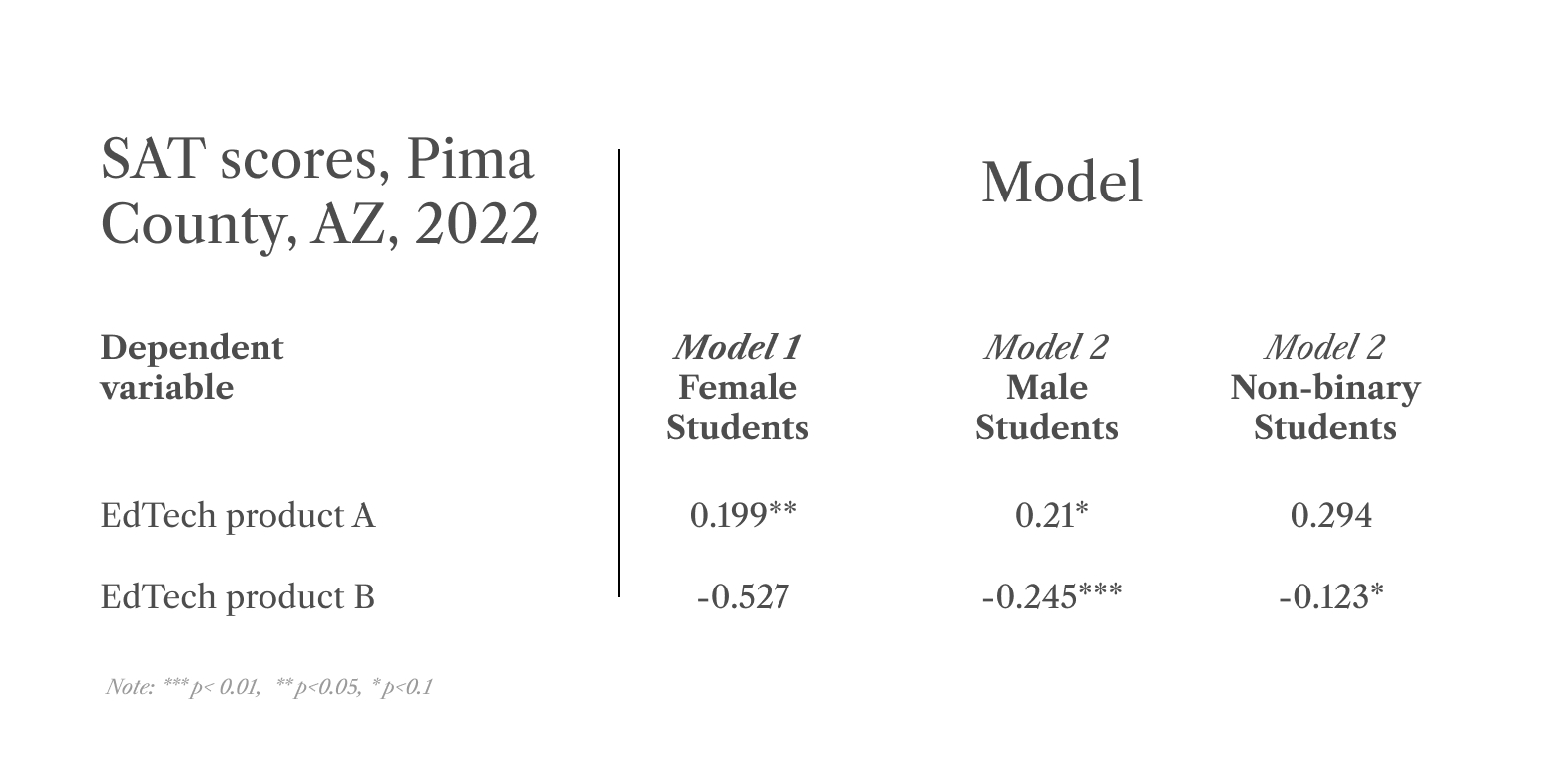

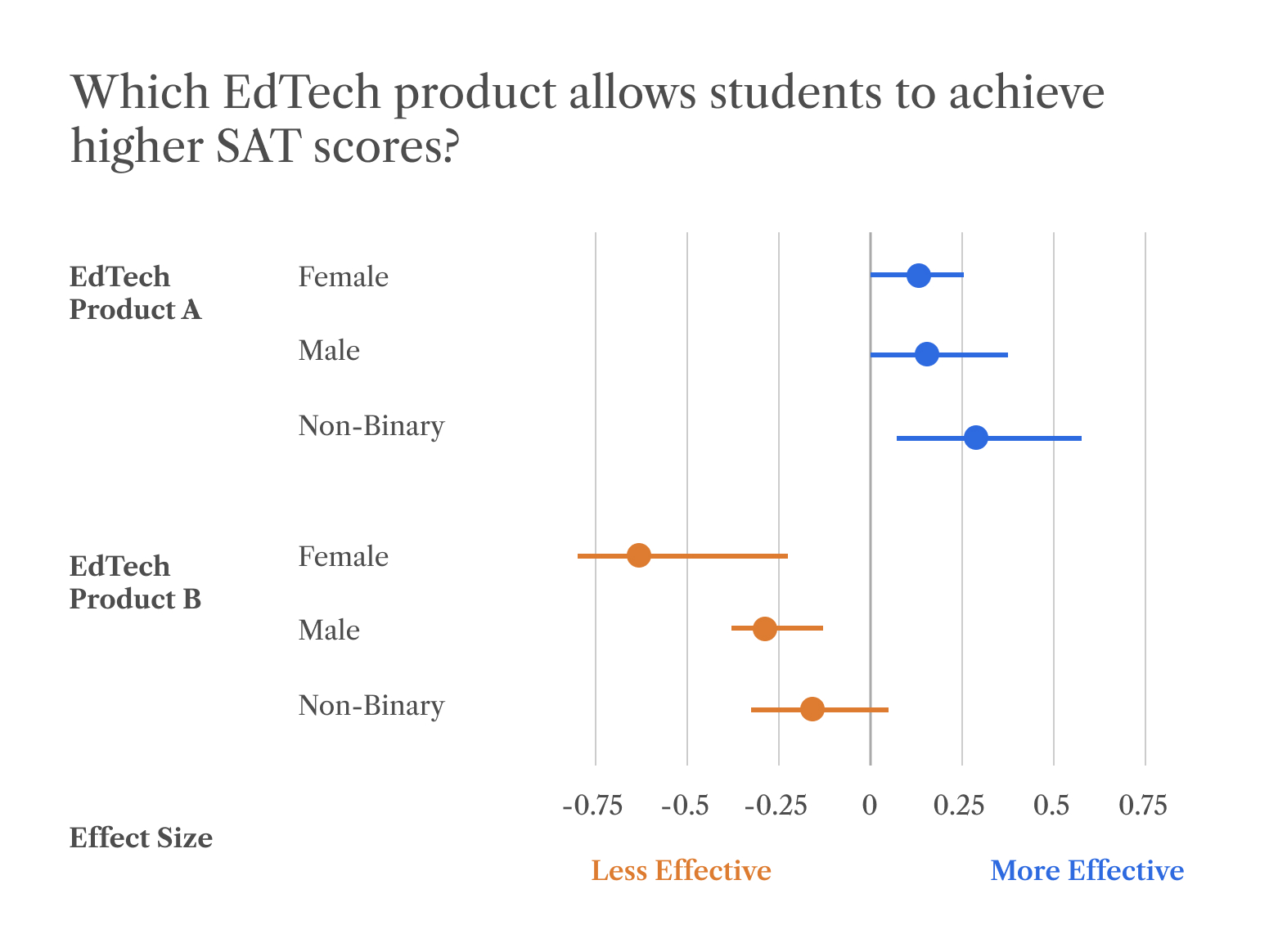

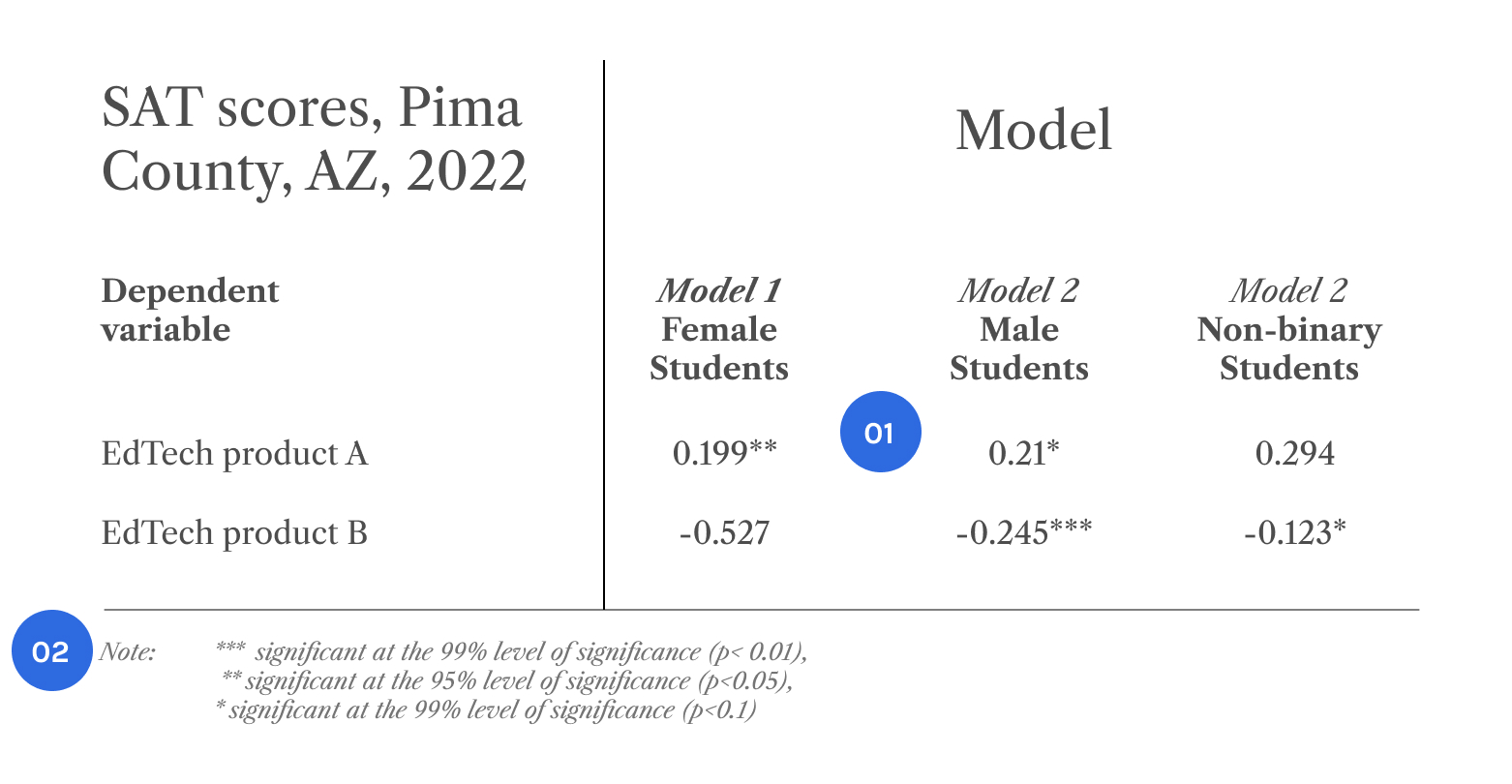

Statistical significance in data determines whether an observed phenomenon is directly caused by a factor of interest or not. Researchers use the term “statistically significant” when they are highly confident that the observed results are not due to chance.

Including information on whether evidence has been found to be statistically significant or not can be a helpful signal for evidence users on whether to rely on those specific findings in their decision-making.

Principle 04

Evidence creators should ensure that the output of research is comprehensible to different audiences which may have varying levels of expertise with statistical concepts.

In order to enhance the accessibility of research, evidence users should adhere to the following principles: